“The aim of life is to find happiness which means to find interest. Education should be preparation for life.”

–A.S. Neill, founder of Summerhill

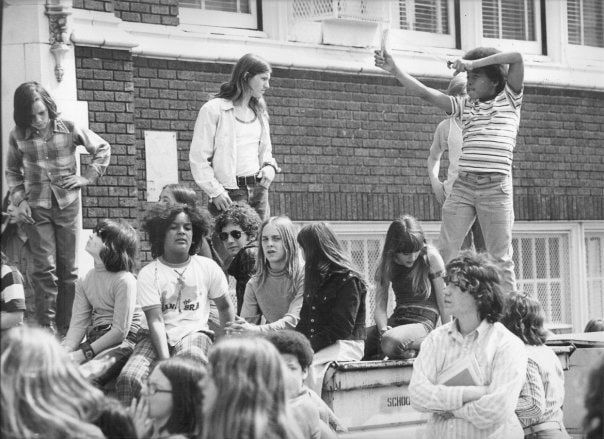

Metropolitan Learning Center formed at a zeitgeist in the American culture. Educators in Oregon struggled with the shift in the culture where a one-size-fits-all philosophy of curriculum left many children behind, uninterested, or disenfranchised. Small experiments with individualized learning had popped up in schools around Portland (in particular at Fernwood Elementary and Cleveland High School) in the 1960s but nothing on the scale of MLC had yet been attempted.

–A.S. Neill, founder of Summerhill

Metropolitan Learning Center formed at a zeitgeist in the American culture. Educators in Oregon struggled with the shift in the culture where a one-size-fits-all philosophy of curriculum left many children behind, uninterested, or disenfranchised. Small experiments with individualized learning had popped up in schools around Portland (in particular at Fernwood Elementary and Cleveland High School) in the 1960s but nothing on the scale of MLC had yet been attempted.

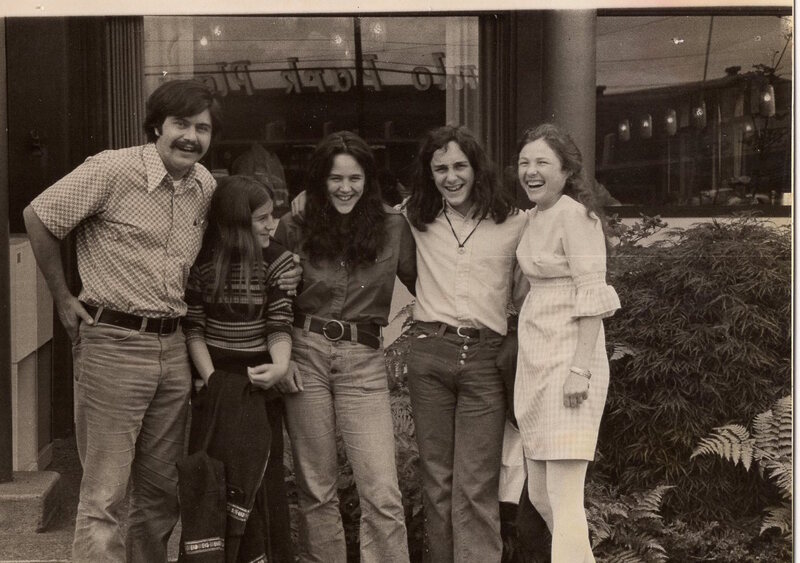

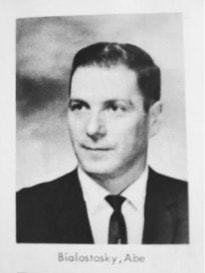

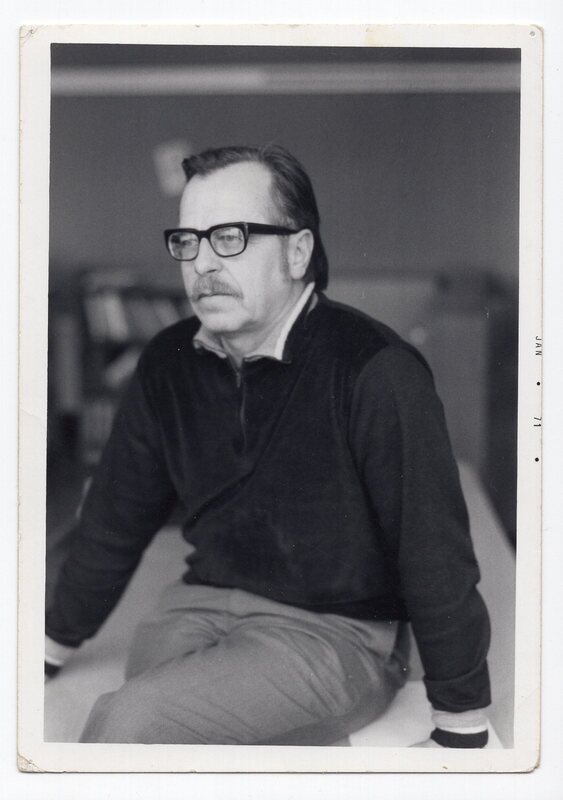

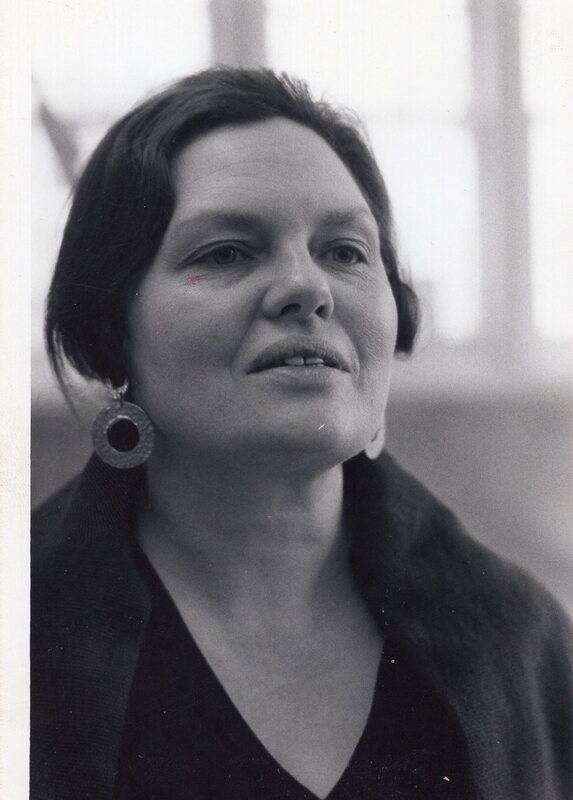

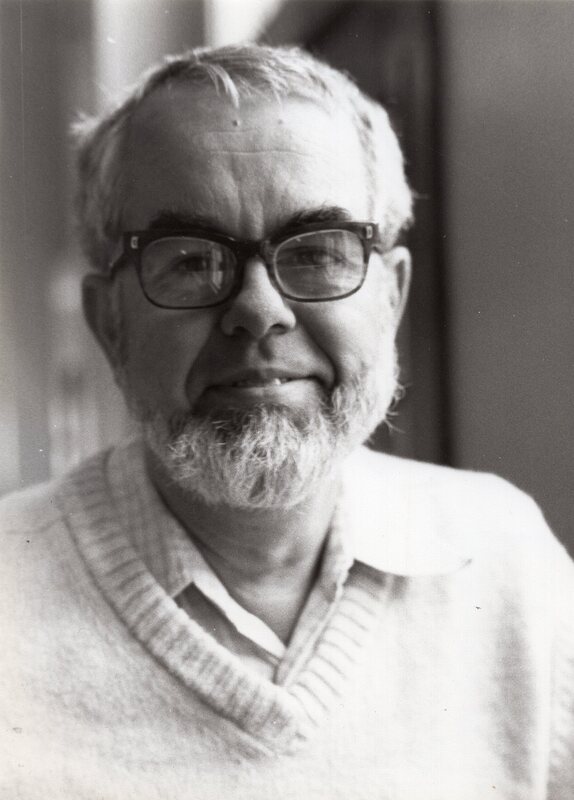

Two Portland teachers, Emil Abramovic and Abe Bialostosky, first met as active members of the teacher’s union. The men spent two years from 1967 to 1968 building a coalition of like-minded civic leaders with the intent of providing an “enriched environment for students where they [could] individualize their patterns of learning and self-development.”

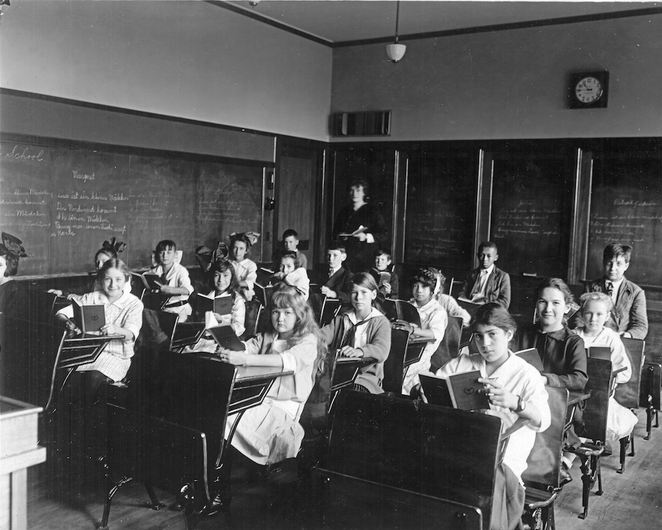

Couch School, circa early 1900s

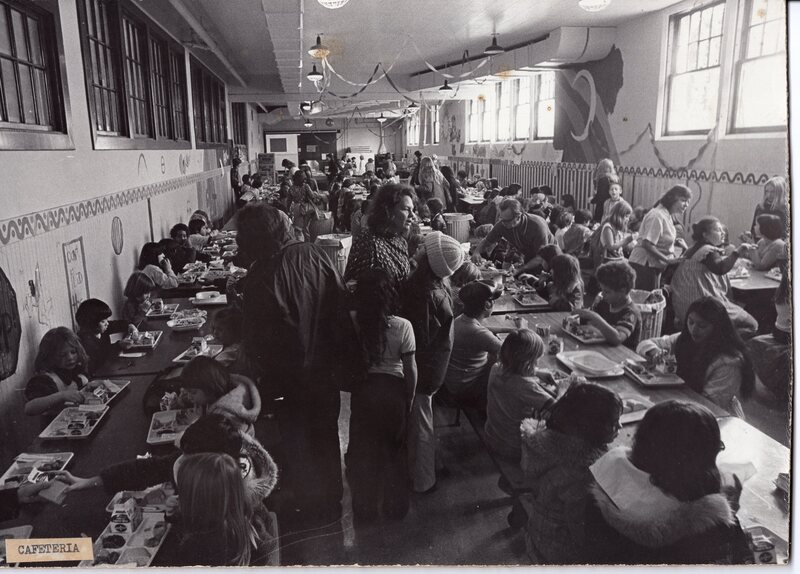

Couch School, a K-6 in Northwest Portland was not the planners’ original choice for the site. Initially, the Center was to occupy two campuses: one at OMSI (then located in Washington Park where the Portland Children’s Museum is now) and the other at First Methodist Church on SW Jefferson Street. Students from Couch School could enroll in the Center as well as a cross-section of students from the tri-county area for a total of 150 children.

Couch School continued its conventional program on the second floor and the Learning Center operated on the first floor. Not unsurprising, tensions existed from the start between children upstairs who envied the looser environment downstairs as well as the resentment that comes with the feeling of one school community invading another.

Couch School continued its conventional program on the second floor and the Learning Center operated on the first floor. Not unsurprising, tensions existed from the start between children upstairs who envied the looser environment downstairs as well as the resentment that comes with the feeling of one school community invading another.

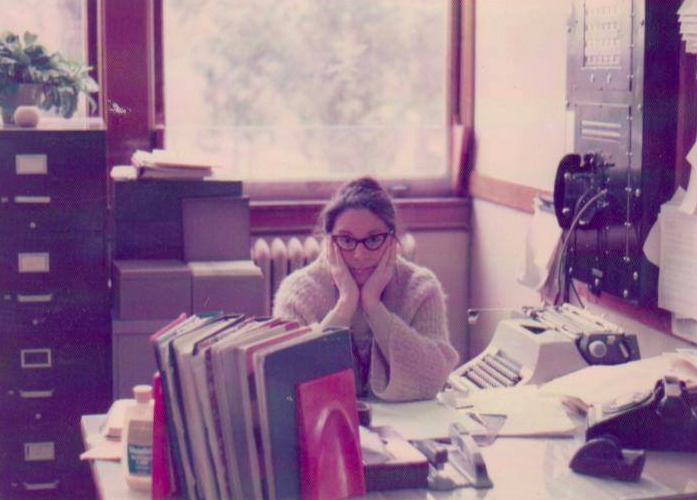

Summer of 1968 found Couch School’s principal, Amasa Gilman, Emil, Abe, and teachers Ehrick Wheeler, Betty Mayther and Sally Svitavsky planning for opening day. “Before we went to Washington Park each day we shopped for good wine and French bread to complement the vegetables from Emil’s garden,” recalled Betty. “The talk at these planning sessions was truly amazing.”

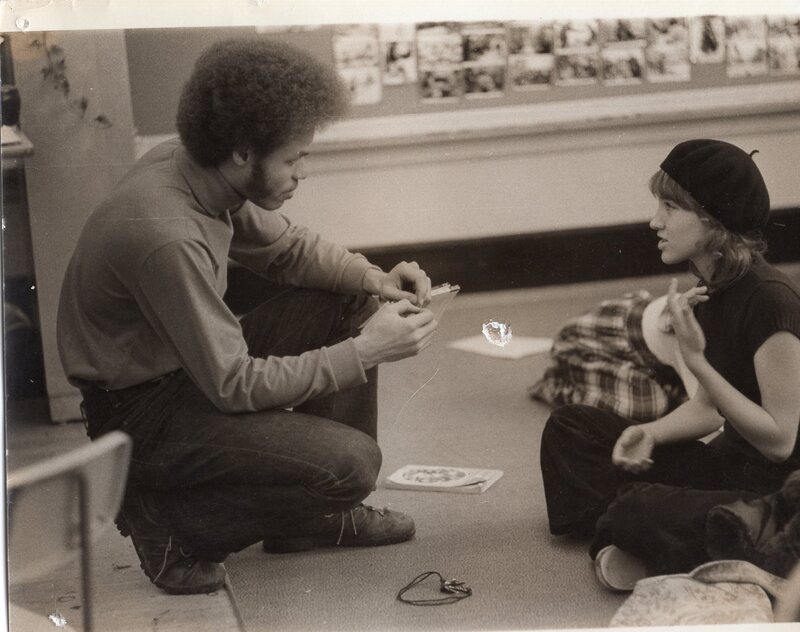

Teachers were expected to be a part of the faculty as well as the community. As noted in the MLC proposal, “One main objective of the Center is to dissolve the walls which normally separate the educator from the community.” Emil wrote consistently of MLC as a community school where students and teachers were expected to both utilize and serve the community. “There is no way to know oneself better than in communication and service to others. We should set up lofty goals for each of us and for MLC itself,” wrote Emil.

Teachers were expected to be a part of the faculty as well as the community. As noted in the MLC proposal, “One main objective of the Center is to dissolve the walls which normally separate the educator from the community.” Emil wrote consistently of MLC as a community school where students and teachers were expected to both utilize and serve the community. “There is no way to know oneself better than in communication and service to others. We should set up lofty goals for each of us and for MLC itself,” wrote Emil.

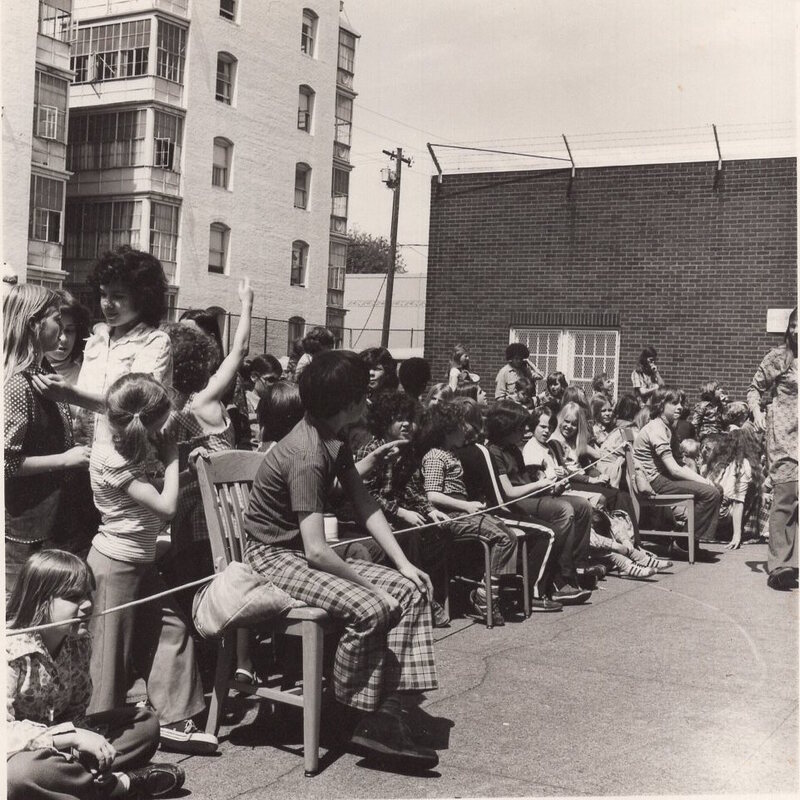

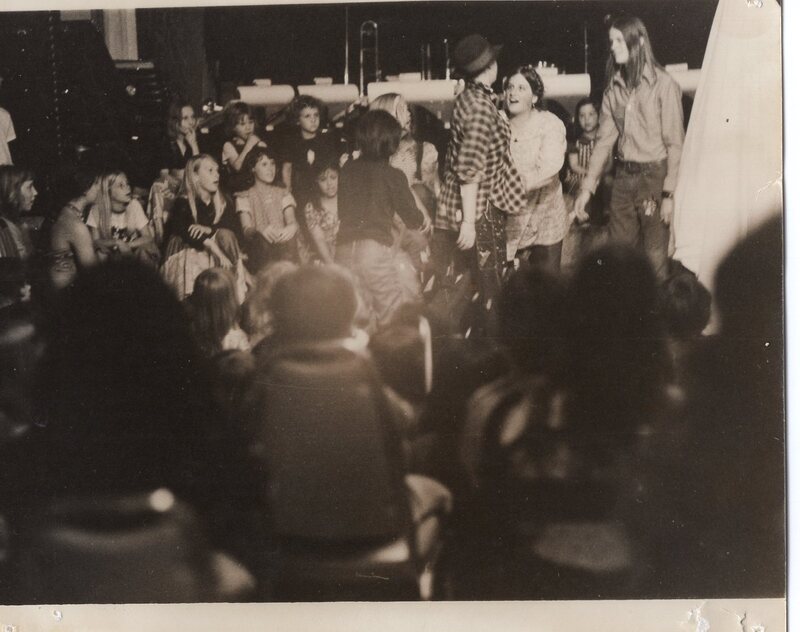

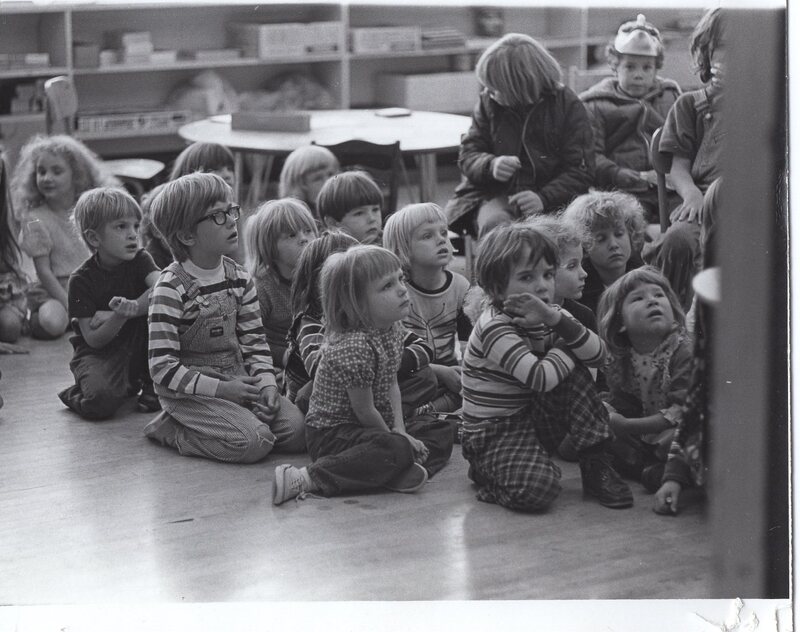

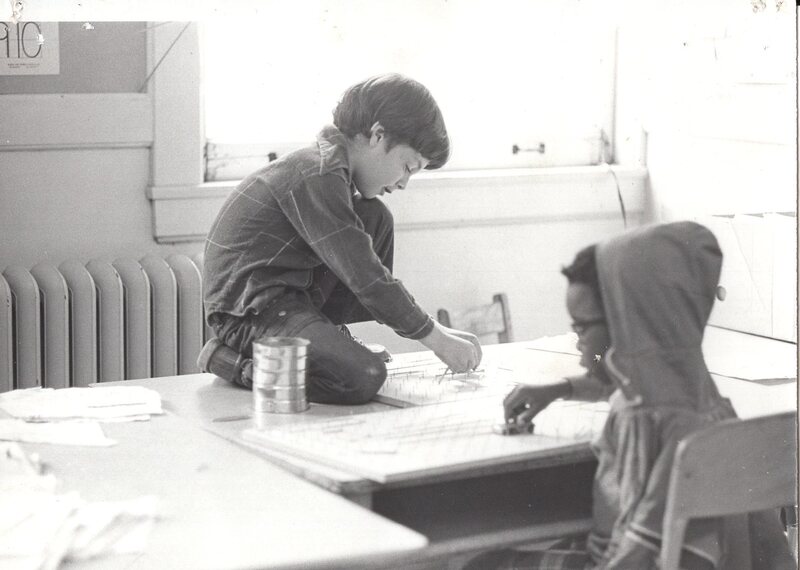

In an age when the gold standard of teaching put a stern disciplinarian in front of rows of seated and silent children, the vision of MLC defined teachers’ roles ideally: “Teachers will encourage students to make individual and group decisions on every aspect of the curriculum. Independence, with a spirit of cooperation and democracy will prevail at all levels.”

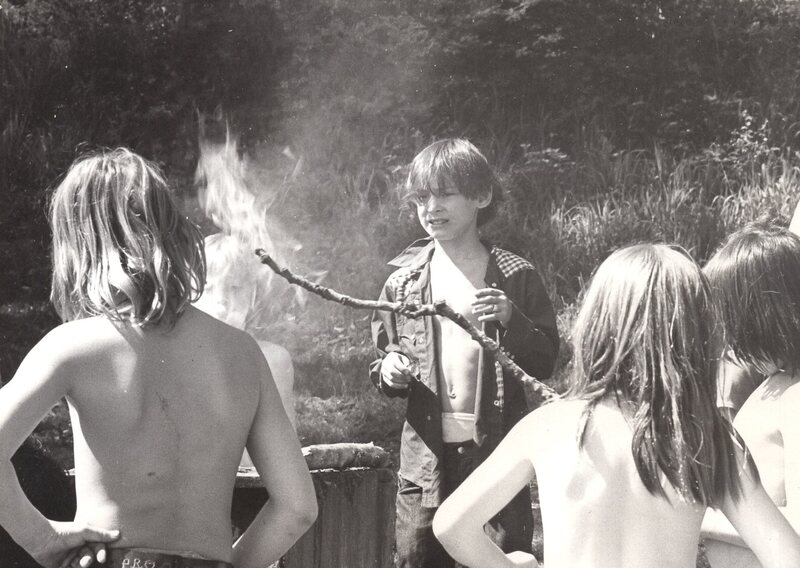

MLC’s democratic school environment, one where a child’s ideas were taken as seriously as an adult’s, had its roots in the philosophy of Summerhill, a “free school” founded by A.S. Neill in Germany in 1921 and soon moved permanently to England. His idea that children have control over their own lives—and by extension, their education—resonated with MLC’s founders. They incorporated Summerhill’s model of self-direction where a student was free to learn and play as they pleased and not necessarily within the confines of a traditional classroom.

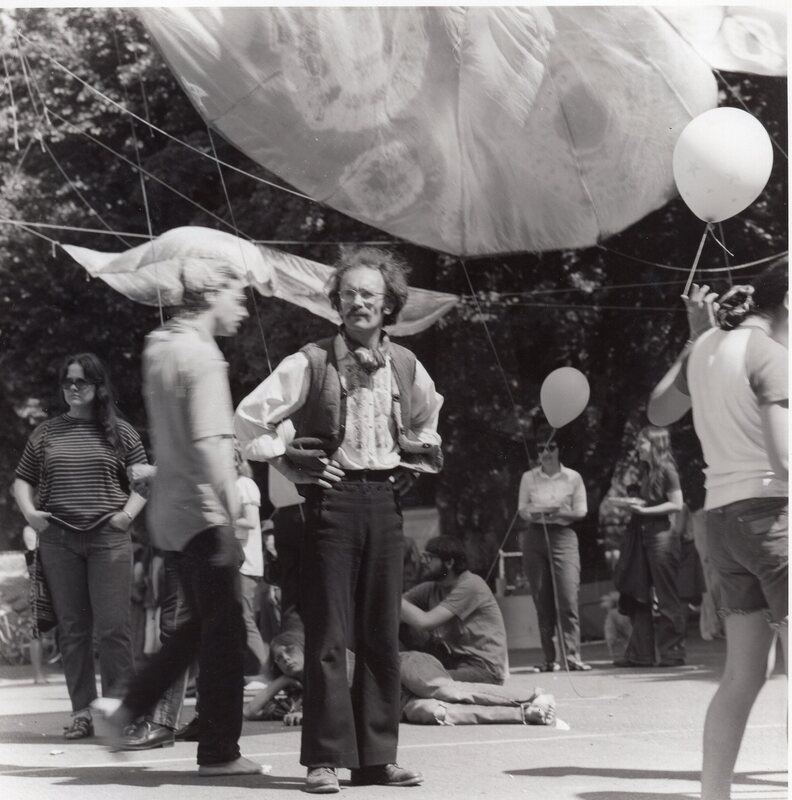

Finally, after years of planning, discussion and thoughtful care, the first day of school arrived in September, 1968. It's the oldest continually operating public alternative school in the U.S.

“In the beginning of MLC, I envisioned a place where people of all ages and pursuits could come together to behold, experience, enjoy and learn from one another,” wrote Amasa. “There were moments, like divine instants, when MLC did fulfill my vision.”

MLC’s democratic school environment, one where a child’s ideas were taken as seriously as an adult’s, had its roots in the philosophy of Summerhill, a “free school” founded by A.S. Neill in Germany in 1921 and soon moved permanently to England. His idea that children have control over their own lives—and by extension, their education—resonated with MLC’s founders. They incorporated Summerhill’s model of self-direction where a student was free to learn and play as they pleased and not necessarily within the confines of a traditional classroom.

Finally, after years of planning, discussion and thoughtful care, the first day of school arrived in September, 1968. It's the oldest continually operating public alternative school in the U.S.

“In the beginning of MLC, I envisioned a place where people of all ages and pursuits could come together to behold, experience, enjoy and learn from one another,” wrote Amasa. “There were moments, like divine instants, when MLC did fulfill my vision.”

Learn more about MLC!

The MLC Magazine was created in celebration of MLC's 50th year.

| 50yearsofmetropolitanlearningcenter.pdf | |

| File Size: | 69882 kb |

| File Type: | |

METROPOLITAN LEARNING CENTER

A Public Alternative K x 12

Since 1968

2033 NW Glisan St. • Portland, OR 97209

Main office phone: 503.916.5737

A Public Alternative K x 12

Since 1968

2033 NW Glisan St. • Portland, OR 97209

Main office phone: 503.916.5737